Context Embedded vs Context Reduced Reading Instruction

The release of John Sweller’s recent report about inquiry learning has been followed up with a range of tweets, Facebook posts and articles either coming out in favour of either explicit teaching or inquiry learning. In this post I am going to share my own thoughts on this in a way that I hope is measured and nuanced. But let’s be clear, I am not going to go down the road of ‘teachers use a range of techniques based on what they believe is best for students so just leave them alone to make their own decisions’. The reality is that, while teachers do make about a billion decisions every day about what is best for students, we don’t get to just put our hands on our hearts and ‘feel’ our way to effective teaching. We must be guided by the research evidence of how people learn, the examination of robust and valid data and the needs of the students in front of us. After all, every school’s context will be slightly different and how we implement those all-important research findings in our school may well look different from how they do it in the school down the road.

Rather than get caught up in the debate about absolutes around explicit vs inquiry, I'd much rather consider things through the lens of context embedded or decontextualised teaching. In reading instruction, this idea is one that can cause no end of debate.

Fully guided reading instruction gets results for the largest number of children. Full stop. This article by Clark, is a really great outline of how and why that’s the case. You might also like to have a look at my previous post about Stanislas Dehaene’s 4 Pillars of Learning. Now, that's not to say that we don't give children the chance to experience reading in informal, low stakes ways that work for them. If a child wants to sit with their favourite picture book for an hour retelling the story, then that's great. But it's probably not going to teach them to read. If we want to embed provocations that encourage reading and writing into our play-based learning, that’s a beautiful thing. But it won’t teach most of our kids to lift the words from the page. If we want to extend our year 1-2 students’ development with challenging text during science, that’s actually an important thing to do, but doing so without scaffolding, support and some decontextualised word level ‘priming’ is just going to overwhelm students who aren’t yet ready for it.

As in all things, we do need to consider the idea of ‘different strokes for different folks.’ Novices, students with learning difficulties and those who don’t have a great deal of background knowledge and skills benefit the most from fully guided instruction. When it comes to the children we teach to read in the early years the vast majority of them are going to be novices. Therefore, we need to provide fully guided (explicit) instruction in reading. Immersing them in literature and providing opportunities for ‘noticing’ the patterns in words isn’t going to cut the mustard. Now of course, everyone can point to the 2 children in their classroom who just seem to ‘pick up’ learning to read as an example that low or partially guided instruction works. However, the challenge there is that we don’t only teach those children. We need to provide instruction that teaches the whole class regardless of processing speed, working memory capacity, socioeconomic background or whether they watch documentaries at home. Every child deserve instruction that responds to their learning needs.

At the start of this post, I promised you a measured approach to the context embedded vs explicit approach, so here goes.

- The same beautifully rich language opportunities that have always been important for early literacy development are still important. Reading engaging books, providing opportunities for dramatic play and the chance to experience reading and writing in ways that are authentic for children are all still wonderful things to do. However, the vast majority of children are going to need a more explicit approach to learning to read. This is going to involve some decontextualised instruction.

- Pointing out spelling and how language works (both orally and in the written from) during shared reading is a valuable undertaking. It enables our students to see the things we have been teaching in context and gives them the big picture of why they are learning what we are teaching. But this, in itself, is not sufficient to ensure that children learn what they need to learn to become proficient readers.

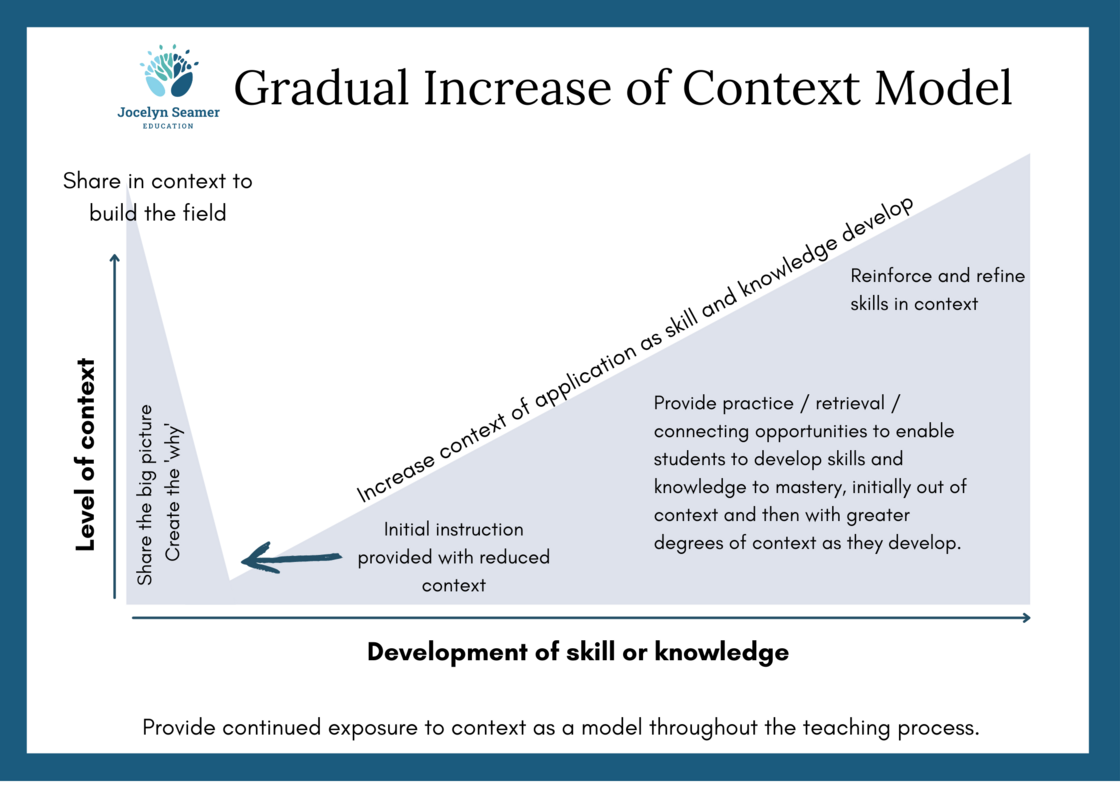

- Context is as important as it ever was, but explicit teaching enables us to help children learn skills and knowledge in manageable chunks without overloading their cognitive loads. So instead of thinking of context embedded teaching as bad and context reduced teaching as good, let’s think about it as an adjustment of context to suit the needs of learners at particular stages of development.

When we first learn something, being able to see the big picture as we build the field is actually important. Then when it comes time to teach skills such as phoneme/grapheme correspondence, blending and segmenting words and sentence structures, we teach out of context. This supports cognitive load and enables children to pay attention to what’s important. As children develop some automaticity, we can support them to apply the skills in increasing amounts of context (short sentences, simple texts, more complex texts). Context isn’t bad and it isn’t good. When we remove the judgement from the equation, we can see that context has an important place – once fundamental skills have developed.

When we consider reading, an inquiry, contextualised, discovery or ‘balanced literacy’ approach advantages those children from more privileged homes who have the chance to build knowledge of the world. It also privileges those children who have the protective factors (thanks Lyn Stone) of brains that put things together without too much effort. This is as true for the early years as it is for upper primary and secondary school. The evidence is clear that teacher led, structured & systematic teaching is what gets it done for our novice learners. My suggestion with the model above, is that novice learners aren’t only our young students. Every time we learn something new, we become a novice learning all over again. As we grow our bank of background knowledge and skills, we have more to draw on as we learn and are able to move from novice to proficient more quickly.

There are few issues that are 100% black and white in our profession. The idea of context vs decontextualised and explicit is no exception. I hope that my Gradual Increase of Context model helps you be a little clearer about the role of context and when to introduce it in your classroom.

You can download a PDF of the model below.

Jocelyn Seamer Education

Jocelyn Seamer Education

0 comments

Leave a comment