Is this the Science of Reading?

One of the most common questions asked in Facebook groups about literacy instruction is “Is this a science of reading resource?” It’s a question that usually ends up with a variety of answers ranging from, ‘No! Don’t touch it!’ to ‘Ooooh, I love that one’. Neither of these answers is very helpful if you are the teacher trying to wade your way through complex decision making to get the best outcomes for your students. This week I’d like to provide a little information and some ideas to consider when making decisions about whether a resource or program is evidence aligned.

Firstly, let’s clarify what the Science of Reading actually is. I can’t say it any better than Louisa Moats, so read her quote below

"The body of work referred to as “the science of reading” is not an ideology, a philosophy, a political agenda, a one-size-fits-all approach, a program of instruction, or a specific component of instruction. It is the emerging consensus from many related disciplines, based on literally thousands of studies, supported by hundreds of millions of research dollars, conducted across the world in many languages. These studies have revealed a great deal about how we learn to read, what goes wrong when students don’t learn, and what kind of instruction is most likely to work the best for the most students."

Of ‘Hard Words’ and Straw Men: Let’s Understand What Reading Science is Really About by Dr. Louisa Moats on Oct 16, 2019 https://www.voyagersopris.com/blog/edview360/2019/10/16/lets-understand-what-reading-science-is-really-about

We can’t walk into the ‘science of reading’ faculty in our local university, but we can read about the findings of research to identify practices that will lead our students directly to proficient reading. For that reason, rather than talk about ‘the science of reading’, this post is going to refer to evidence informed practice as a way to describe the kind of instruction that is likely to be most helpful to the most students.

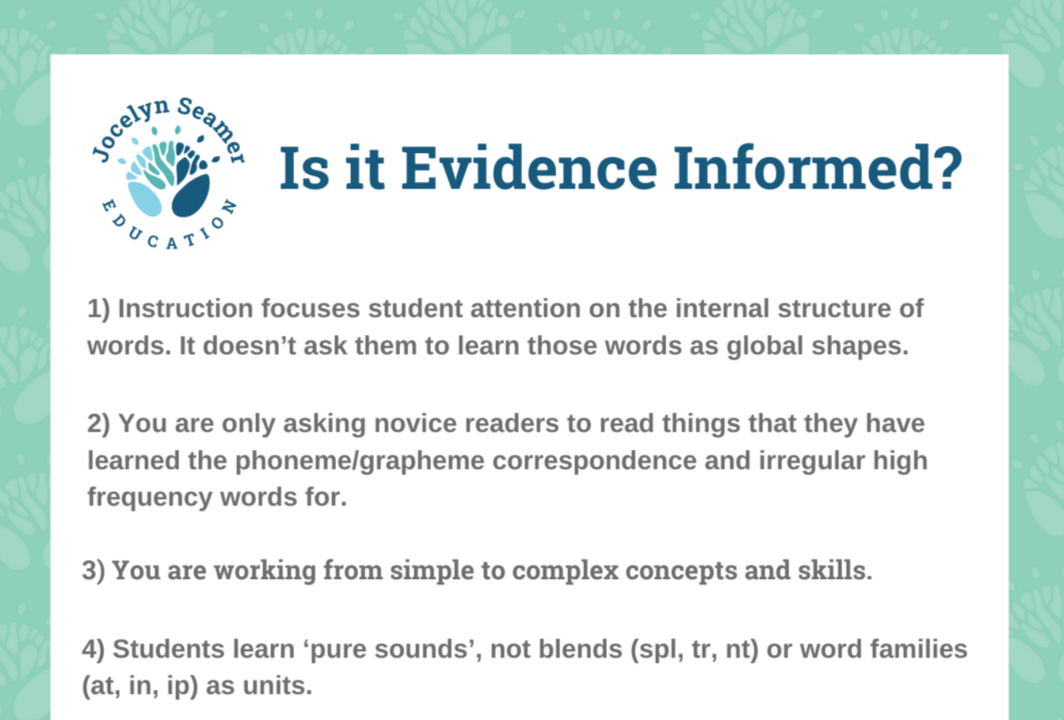

Here are some key things that you should be looking out for when choosing resources and techniques for your classroom. The first 5 points relate to the ‘what’ of reading instruction. The second 5 relate to the ‘how’:

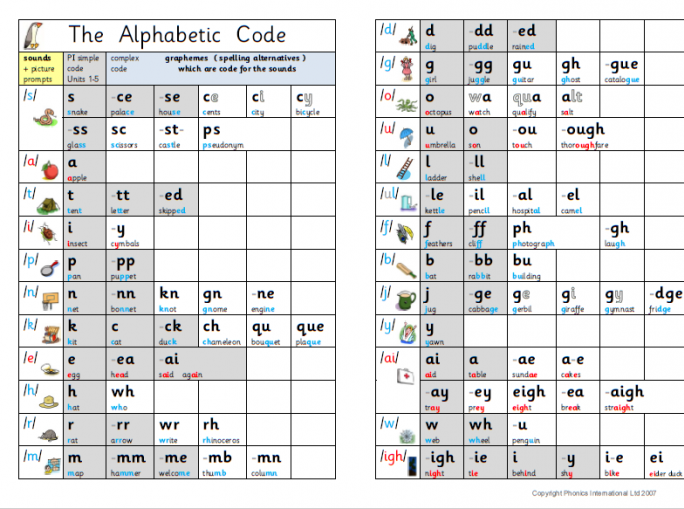

- Instruction focuses student attention on the internal structure of words. It doesn’t ask them to learn those words as global shapes.

Over time, students will come to internalize the patterns of words and recall them automatically, however the path to this automaticity is knowledge of the alphabetic code. Linnea Ehri describes this knowledge as the ‘glue’ that binds word recognition. Stanilsas Dehaene’s research shows that even as proficient readers, we process words via sounds, but we process every sound in the word at once instead of one at a time. It takes 2-3 years to develop this automatic reading. To fully develope this knowledge, we include blending and segmenting with graphemes in our decoding lessons, right from the start.

- You are only asking novice readers to read things that they have learned the phoneme/grapheme correspondence and irregular high frequency words for.

Students are novice readers until they know most of the complex code and are building fluency. You may need to apply this guideline for longer for at-risk readers.

- You are working from simple to complex concepts and skills.

Cognitive load theory tells us that it’s important to optimize the difficulty of a task. We do this by not adding too many new pieces of information at once and not increasing the complexity before students are ready. In reading, this takes the form of learning the simple alphabetic code before the complex one and reading texts with simpler vocabulary and sentence structure before diving into rich texts. (We read these TO students until they can read them for themselves.)

- Students learn ‘pure sounds’, not blends (spl, tr, nt) or word families (at, in, ip) as units.

Teaching blends and word families as ‘units’ adds a significant amount of content for students to learn and misrepresents how the alphabetic code works. Over time, students will commit these patterns into long term memory, but as with point 2, this occurs through great phonics teaching that includes explicit teaching of phoneme/grapheme correspondence and blending & segmenting with graphemes in every lesson.

- Instruction provides the most direct path to learning.

All too often, the activities we give students to do are not ‘bad’ in and of themselves, but they might not necessarily provide the most direct path to learning. An example of this is cutting up sentences, putting them back together and then copying them. Sure, a student might be decoding the words and placing them in correct order (a seemingly good thing), but is this the most direct path to learning? I’d suggest that simply reading and writing sentences as part of a systematic lesson would be a better use of instructional time and help students consolidate skills much more effectively.

- Your instruction meets students at their point of need, providing sufficient practice and review to enable learning to mastery.

Stanislas Dehaene’s 4 pillars of learning, provide a framework for strong learning. Opportunity for consolidation is a critical factor in learning. Without it, learning is never transferred to long term memory where it can be retrieved automatically, freeing up our attention to focus on other things.

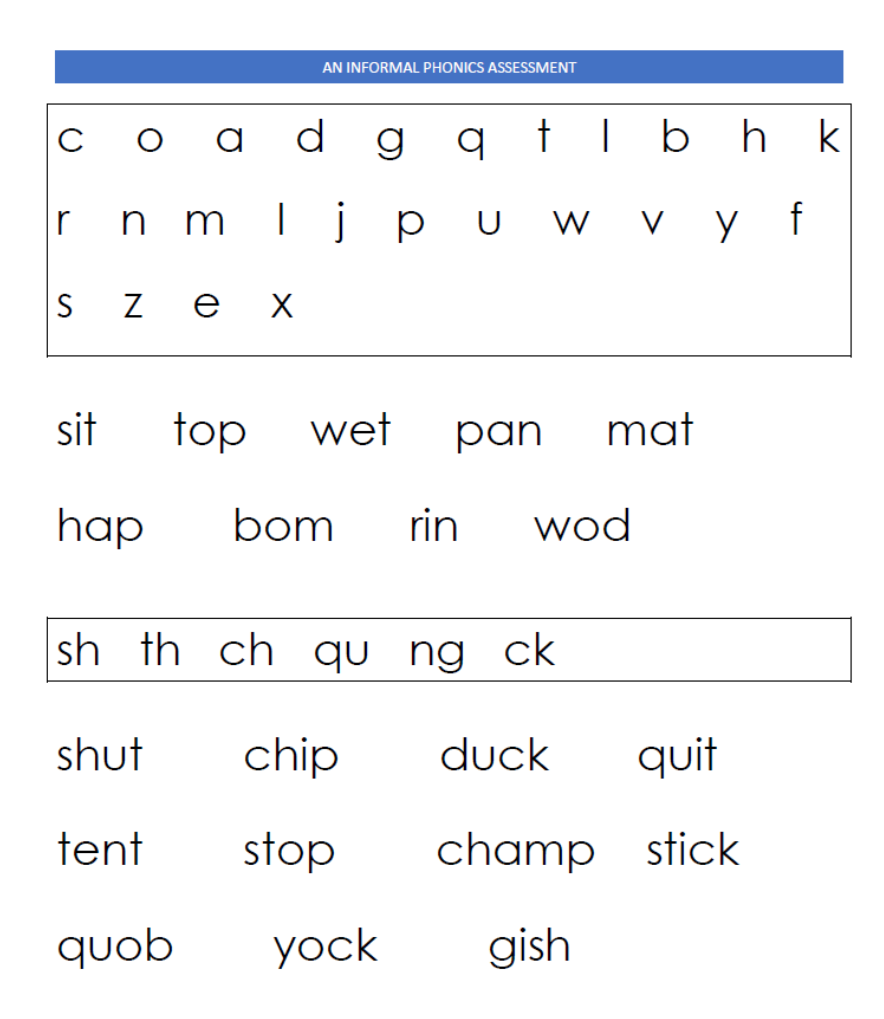

- Decisions made about content and method of instruction respond to assessment data, rather than the timing of a program.

Any program is simply a tool with strengths and limitations and no program replaces your skill as a teacher. Part of that skill is tuning in to your students’ learning needs as revealed through targeted assessment. This data collection might be formal or informal, but will be regular, reliable and inform future teaching.

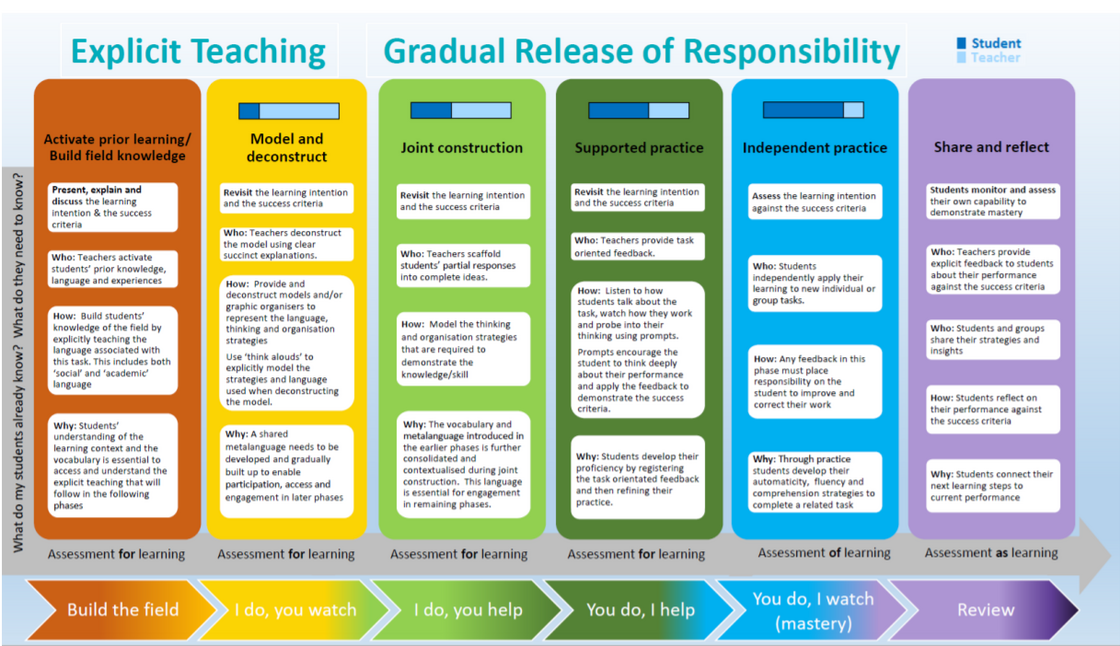

- Learning is delivered via fully guided instruction, rather than providing activities for students to do on their own.

This guideline comes back to Dehaene’s four pillars. Our role as teachers is to direct student attention, ensure full engagement, provide error correction and facilitate consolidation. There is simply no way that we can do this if we are not directly teaching our students.

Graphic courtesy of Education NT

- Instruction takes the form of explicit, gradual release of responsibility and includes I do, we do, you do.

Explicit teaching is supported by a vast body of research. Far from being a boring, disengaged method of teaching, explicit instruction ensures that students are supported and that learning is scaffolded so that students may focus on the most important content. The I do, we do, you do framework protects students from cognitive overload, while remaining focused on continual growth in learning.

- Every student will be actively engaged in learning, with their attention focused on the skill or knowledge being developed.

If we put points 6, 7, 8 and 9 into action, this guideline will be evident.

The above 10 guidelines are not meant to be an exhaustive list of elements of evidence informed practice in reading instruction, but are intended to provide you with a quick and simple reference when you are making decisions for your classroom. You can download a poster of the key points for your staffroom or classroom below. Happy Teaching!

Jocelyn Seamer Education

Jocelyn Seamer Education

0 comments

Leave a comment