S3 Ep18 - Explicit Instruction That Doesn't Come At The Expense Of High Flyers

Hello and welcome to the Structured Literacy Podcast, the podcast where we keep it real about what it's like to shift practice and teach in a way that reflects evidence from research. As much as I'd like to give you a set of general principles about instruction that will work perfectly in every situation in school, I'm afraid it doesn't actually work that way. Yes, there are some considerations and principles about instruction that apply across contexts that work no matter where you are or who you're teaching, but there are also many aspects of instruction that vary from place to place and classroom to classroom. For example, we know that explicit teaching is highly effective for all students. Everyone, everywhere, benefits from being taught in a direct, unambiguous way while they're a novice, and for us in the primary school, that's everyone. Research has consistently found that explicit and direct teaching has the greatest benefit for the largest number of students. Similarly, taking a knowledge-rich approach to teaching and intentionally building students' declarative knowledge across all areas of the curriculum makes it easier for students to be skilled in reading and writing. Understanding these principles helps us make critical decisions about what instruction looks like in our schools, what kind of professional learning to provide, where to focus teacher development and what kind of resources to source.

However, there are other ways and places that we don't have as much guidance, and it's these that leave teachers worried and often hesitant to take action.

One of the concerns that I've heard expressed in recent weeks is around the impact of explicit, structured teaching on our higher-flying students. Teachers have said things like,

"I'm worried that we're making the classroom boring for our more capable students,"

or,

"How is it equitable to ask students to participate in lessons about things they already know because other students don't know them,

and then

"Where's the engagement in learning?"

These questions and comments are not used as pushback at being asked to adjust instruction, they aren't an indication of a teacher's lack of commitment to their students or to their job. They are genuine wonderings about what a shift in practice means for students and means for them. I think that they're fair and reasonable and that the questioners raise some very valid points. In this episode, I'll be sharing some thoughts and practical actions to help you and your team navigate the often choppy waters of moving to a knowledge-rich, explicit approach to teaching students to read and write.

Let's start with the impact of explicit teaching on high-flying students. The number one reason, in my book, to provide explicit, knowledge-rich teaching to high-flying students is that it enables them to fly higher, faster and with more skill. All students learn in roughly the same way, but with differing levels of ease and speed. All novices benefit from being taught in a direct way. Higher-flying students may simply not need the same level of intensity and the same amount of guided practice as their peers. My observation of high-flying students is that they look like they're doing well, and probably are, but they can have more difficulty than they need to when it comes to applying new learning into unfamiliar contexts.

In last week's episode of the podcast, I suggested that many students who appear to have it all together when it comes to spelling may well be running on instinct. They can spell words and do things with those words, but they likely don't know how or why words are constructed the way they are. This makes it harder for them to transfer and apply new learning across a range of contexts. So that's the benefit of explicit, knowledge-rich teaching for those students:

It builds the how and why that brings them on faster and stronger.

The Errors We Make

The error that I think we make in our teaching when it comes to high-flying students is that we assume that they don't need all that direct teaching. Well, actually they do.

The difference between them and others is that they don't necessarily need all the hand-holding and careful monitoring of practice and review that other students do. They can apply what they've learned quicker and more independently.

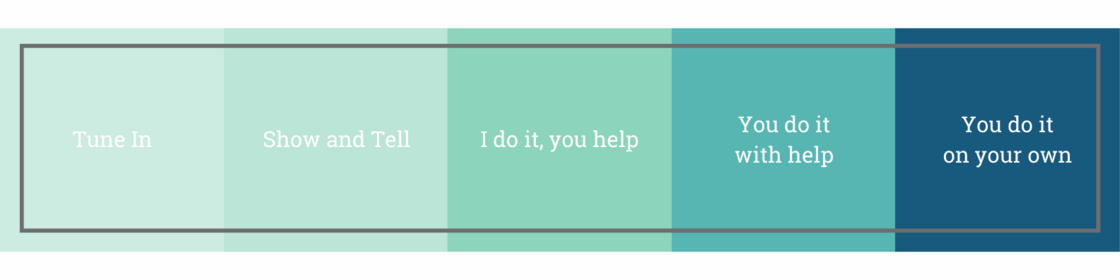

The framework that we can use here to help guide our practice is the explicit teaching model itself.

That includes:

- tuning in,

- the I do (where we tell and show),

- the we do (where we do something together as a class or with a partner),

- the supported practice (where we follow up, with careful consideration given to intensity, pace and duration) and

- the you do (where students apply new learning on their own in context).

Students don't really vary in their need for these steps, but they do vary in how quickly they move through them. So students who need more help will need simpler instructions, more opportunities for supported practice and careful increases in complexity.

Higher-flying students don't need instructions that are quite as simple, but they don't hurt them.

They need fewer opportunities for supported practice, which doesn't mean they don't need any, and they can make larger leaps in applying new learning in increasingly complex contexts. This doesn't mean that you have to group students to provide separate lessons, but you can consider this in making decisions for teaching. What we're really talking about here is differentiation of support. It's my opinion that in every area of the curriculum, except for initial phonics instruction and early number, teaching can and should occur at whole class level, with differentiation referring to the amount of support provided to different students.

Every student will need to learn about simple sentences. Every student will need to learn about prefixes and suffixes. Every student will need to learn about text structure. Teach all the students together and adjust support as required. Teachers have been instinctively doing this for donkey's years. We teach something to the class, and then, at some point, we plan for students to apply what they've learned. We send some students off to work independently, while others stay with us on the mat. Where we run into trouble is that we've expected to have the time allocation for that to be 10 minutes of introduction and 40 minutes of independent application. I'd suggest that it could look more like 20 minutes of introduction and supported practice, with 10 minutes of supported application followed up by 10 minutes of further instruction and 10 minutes more of application, and that's the breakdown that you could have for most of the class. High-flying students may not need to come back for 10 minutes of further instruction. They may well be able to do half an hour of application as long as there's the opportunity to ask questions and have a check-in.

The next thing I think we can consider is expectations of students with a range of levels of development. Let's take writing, for example. In coaching teams to write their own text-based units, one of the considerations we have is how we're going to adjust our expectations of what students will produce in the summative task for the unit. Let's take a task that involves writing an analytic response to a text. The unit may focus on identifying examples of a language feature, such as subjective language. Students are being asked to comment on whether a selection of written pieces is objective or subjective based on the use of language features in those texts. All students can, with appropriate explicit teaching, scaffolding and support, identify examples of subjective language. Most, again with appropriate explicit teaching, will be able to write about this and the impact on the reader.

The question then arises about whether we should be expecting proper paragraph structure with a topic sentence, explanation examples and a sentence to link to the next paragraph. You may have begun to teach this, but the class isn't yet strong in paragraph structure as a whole.

So what do you do?

My approach to this is to decide on whether expecting full paragraph structure from the whole class will be too much on their cognitive load. We're already asking them to identify examples of subjective language and then construct a written piece around this and comment on the impact on the reader.

This kind of analysis isn't particularly easy. If the majority of the class isn't yet confident in paragraph structure, asking them to use it when it hasn't been a feature of current instruction might be a step too far. However, if our high-flyers have taken to the structure of the paragraph like a duck to water, there's no earthly reason not to ask them to use full paragraph structure. That's not overloading them because they can do it. It's also likely producing a degree of desirable difficulty that challenges them.

After all, if there's no challenge, there's no learning.

My point in this is that it's perfectly okay to have the same overall learning focus for your class and then adjust expectations around more or less complexity in those tasks if the students can actually meet the expectations and it won't overload them. Just because the rest of the class needs additional practice with paragraph structure, it doesn't mean that our high-flyers can't use it.

If your high-flying students can produce more in-depth, more complex writing independently, let them. And the same goes for some phonics review. You may recognize that your students could benefit from a bit of a phonics boot camp in the year three to six space but you've got kids who can work with single syllable words with ease. So within the context of the lesson, have multi-morphemic or multi-syllabic words available to stretch them.

One learning focus but a different level of complexity in application.

The Use of Choice

Another way that you can let your high-flyers stretch their wings a little in application of learning is to give them some more choice. It's very common in years three to six to make tasks quite open-ended for the whole class and then expect students to engage well with learning. It often doesn't work. Too much choice for students very often just adds to their cognitive load. They have to research, take notes, plan and write on their own, and there's only one of you, so you can never get around and help all the students who need it.

The alternative is to have one question or topic for students to write about, and this is great for most students because you can walk them step by step through the task. But for high-flyers, they might feel constrained and a bit resentful of the boundaries being placed on their thinking. Your option here is to engineer a little more wriggle room for them to have more choice and branch out from the main task, slightly. They need to have their idea approved by you, but they can extend out, because they can, they don't need someone walking with them every step of the way.

The next point to consider in terms of engaging our high-flyers is the topics and subject matter we choose to include in our literacy lessons for everyone. When choosing texts as a stimulus for reading and writing instruction, choose texts that contain topics and details students will actually find interesting. As students get older, they enjoy more sophisticated subject matter that they can really sink their teeth into. Being able to emotionally connect with a text means that we want to read more of it. Vanilla texts that don't contain any danger, turmoil, tragedy or drama simply aren't going to hook kids. And of course, you are going to use your judgment to ensure that material is appropriate for students, but don't forget that it has to be interesting.

A classic example of this is in the text The Velveteen Rabbit. This isn't overly complex in terms of decoding, but it does contain themes that take some examination, including authenticity, belonging, identity and loss. Help students connect with lovely texts and they'll be right there with you. And that Velveteen Rabbit text, I use that as an example in our Build the Foundations for your Literacy Block in Year 3 to 6 workshop. And we never fail to have teachers hooked and engaged. If adults are engaged with that text in the way that the lesson is run, the students will be too.

The next point here is to be ambitious for your students in terms of the text that you explore as a class. For so long we were told that we had to match text to students in terms of their reading level. This just isn't true. Once students are through the early decoding part, we need to provide the opportunity for students to engage with rich, inviting texts that are just that bit too hard for them to read on their own. Our worry might be that, in moving to an evidence-informed, inclusive model of instruction, we can't provide challenging reading material because some of our students aren't strong decoders. That is just not the case.

Choose the challenging texts. Choose the texts that make students think. Choose the texts that have themes students can relate to, then provide support for the decoding where necessary. Students who are weak decoders are perfectly capable of engaging with a text with complex themes. Just give them support to lift the words from the page, such as a partner who's reading for them or an audiobook.

And where do we find texts like this? They're all around us.

The challenge is that we really do need to have a copy of the text for every student or pair of students to be able to read and follow along with themselves. They need eyes on the page, and this is why, in the work we do, we favour short stories that are available in the public domain. They're challenging, with sophisticated themes, and we can provide them to you as a PDF, there's no need to purchase class sets of text.

My final thought on making sure that we continue to engage our high-flying learners is about what engagement really means. There is a big difference between engagement and entertainment. When it comes to the classroom, we're looking for students to be actively thinking and doing, not just having a good time. Actively thinking and spending time practicing and refining skills might not be engaging for students who are used to breezing through their day. Their cries of, "This is boring" and "I don't like this" might not be because what you're asking them to do isn't stimulating and engaging, but because you are removing opting out from the equation.

They want to do things once and move on. They want to be the one who knows the answers quickly. They don't like having to slow down, having to have another go and put in effort. When most learning comes easily to students, encountering the situation where they're being asked to edit their first draft, have another go at a second draft and really think about it can feel like the earth is crashing down. The phrase, "'This is boring" might actually mean, "You're making me slow down and think, and I don't like it; I'm used to fairly cruising through the work we do."

Students' assertions that "We've done this" is very different from "I know this". We need our students to understand that learning is a permanent change to long-term memory that is accompanied by consistent, high-level performance. It's not just getting a few right answers and moving on. It's terribly important that we DO challenge our high-flyers to do the hard things and spend time reviewing, revising and consolidating. They need to develop dispositions for learning that set them up for success, because one day they are going to encounter a learning experience that is hard, that's a little beyond them, and they're going to have to put in effort. If we haven't helped them to acquire the necessary habits for learning, they may well fall into a heap when they're older, and that could hit them in secondary school or in tertiary studies.

Moving to a structured approach to teaching reading and writing does not have to come at the cost of our high-flying students' engagement. They benefit from explicit teaching that builds knowledge, because it helps them learn to apply their learning to new contexts. They also benefit from low-variance instruction because the classroom is a calmer place to be. Higher-flying students don't need as much targeted scaffolding in applying new learning, but they do need you to think carefully about how you're going to extend and enrich their experiences. You can do this by giving them some choice, not holding them as tightly to the group as others when you break tasks down, and by choosing rich texts for the whole class to dive into.

Remember, though, that assertions that "This is boring", or "I've already learnt this" need consideration before you go off and change things. All of this contributes to the argument that explicit teaching, really responsive, explicit teaching, can't be scripted. Even having robust resources doesn't eliminate the need for teachers to think about their students and reflect on how to respond to their needs, and that is part of the art of classroom practice.

I love questions like those that prompted this podcast episode. I love it when teachers are brave and say, "Yes, Jocelyn, but..." or "How can I trust this now, when things are changing?" or they just express doubt in general. If we can't do that, we can't move forward together. So we shouldn't be shy about expressing concerns. That's how we grow and develop as a profession.

Do you have a 'yes, but' question that you'd like me to address on the podcast? If you do, get in touch at help@jocelynseamereducation.com and let me know what you're thinking, we really are here to help. Until next time, I wish you all my very best. Bye.

Ready to bring consistent challenging learning to your classroom? Join us inside The Resource Room!

Jocelyn Seamer Education

Jocelyn Seamer Education

0 comments

Leave a comment