Engaging Reluctant Writers

Every classroom has students who hate writing and will avoid it at all costs. They might groan and moan when you say the word ‘writing’ or ask to go to the toilet the minute you need them to sit at their desk. When they do sit down, they take 500 years to write the date and then poke the person next to them or engage in some other off-task behaviour. Their antics mean that you can’t spend time supporting those who WILL engage but need some support or conference with those who are quite capable and need extension. As a teacher, it can take all the fun out of a writing session when reluctant writers disrupt proceedings. Then there are the ‘sit and do nothing’ kids.

They write one or two simple sentences and then just sit there quietly, maybe putting their head on the desk. When you sit with them and ask them guiding questions such as “What else could you write about this?” or “what happens next?” in your most encouraging voice, they say, “I don’t know”, with a pained expression on their face. Or they can tell you about what they want to say but simply can’t get the words down on the page.

These students do not wake up thinking, “Hey, I am perfectly competent when it comes to writing, but I just don’t like it, and I will do everything in my power to make my teacher’s life difficult today”. Odds are, the thoughts going through their heads is “This is too hard.” and “I am so dumb.” Reluctant writers are usually reluctant because they find writing difficult. The reason writing is difficult for them and how to support them can vary.

The Importance of Automaticity

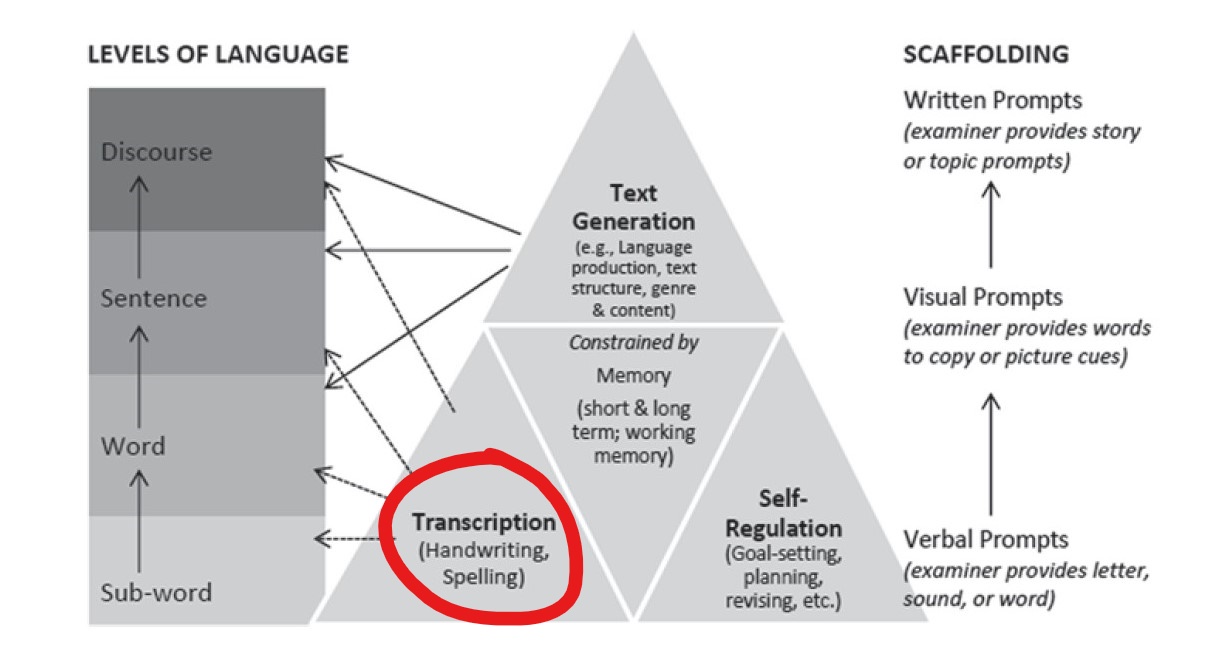

Writing is a highly complex process that requires certain skills to be performed automatically (without conscious thought) to be successful. Each person only has a certain amount of cognitive energy. In order to successfully write, we need to be able to perform a number of tasks simultaneously. When we can only think about one thing at a time (which is the case for all of us), we need to develop some of these tasks to automaticity to give our full attention to the most important parts of writing. That is language and delivering a meaningful message. As we review the areas that children may be experiencing difficulty with, reflect on your students and ask yourself, “Does this student have these processes developed to automaticity?”

Area of Difficulty 1 - Handwriting

Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (1993). Structural equation modelling of relationships among development skills and writing skills in primary- and intermediate-grade writers.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 478–508.

Many students make it to high school with poor letter formation. When a student is spending cognitive energy figuring out how to form individual letters, they are not able to think about spelling, sentence structure or language use. This can result in a very frustrating experience for the student. In this modern age of so-called 21st century skills, schools may either abandon handwriting lessons beyond the foundation year or not teach it all. The reality is that while modern technology does involve us typing, handwriting is still a vital skill to learn for all ages. It is important to remember that handwriting needs to be taught. Providing a handwriting book for your relevant jurisdiction and assigning ‘handwriting’ as an independent activity is not teaching handwriting. Every time a child writes a letter incorrectly, they further entrench poor habits. Your school’s phonics program may have mnemonics for letter formation. Read Write Inc. phonics has very effective rhymes for letter formation that you can find at the link at the bottom of the page. Finding time for letter formation instruction throughout the school week is a very worthwhile undertaking. Handwriting lessons can be easily differentiated so that some students are learning cursive and others are learning printing.

Area of Difficulty 2 - Spelling

When students do not know how to spell effectively, it is not unusual for them to use less complex vocabulary or write far less than they are capable of. Difficulties in spelling could point to any of the following:

- The student does not have sufficient phonemic processing to be able to pull the word apart orally and identify the sounds they hear (segmenting)

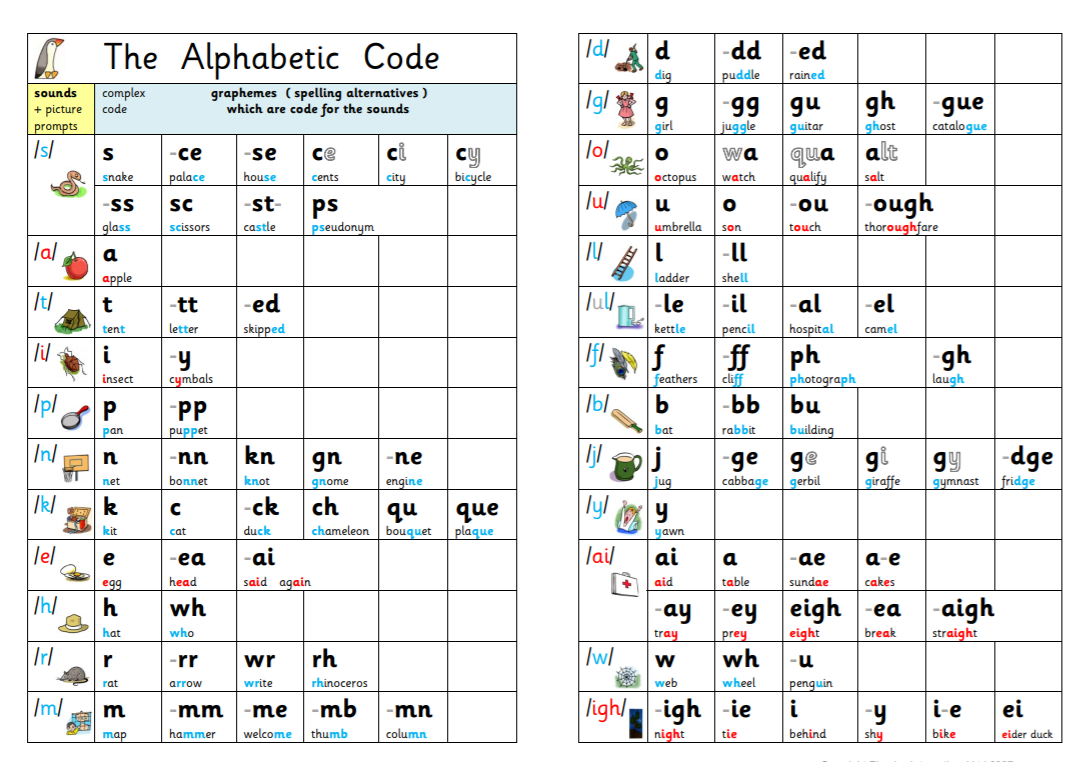

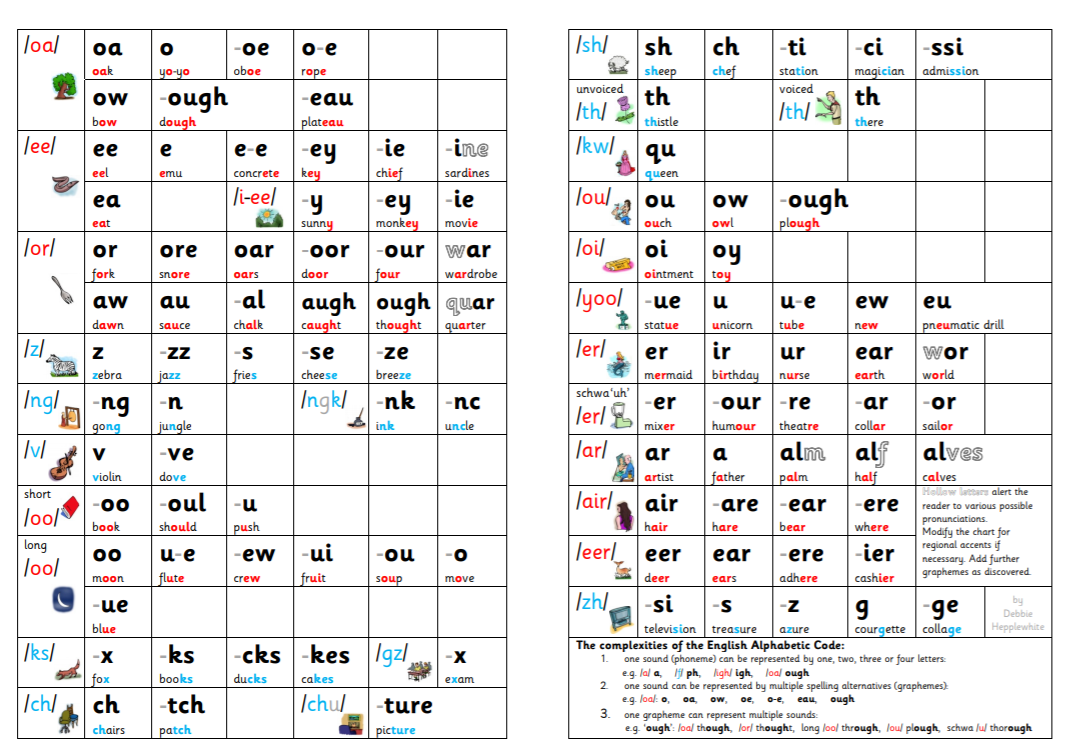

- The student does not have sufficient knowledge of the alphabetic code to know how to write down the sounds they can hear. To represent words on a page, students need to know at least one representation of all 44 phonemes of English. In order to spell correctly, students need to have a complete understanding of how words work, including a confident recall of the most common representations of English speech sounds. The charts below show just how many representations there are to learn. These must be taught explicitly in quality word study and not just included in send-home spelling lists. In fact, weekly spelling tests are not necessary at all. Teach phonics in a rigorous way with reading and spelling included as reciprocal processes, and you will never have to have a Friday spelling test again!

- The student does not have sufficient awareness of other spelling concepts such as morphology (including prefixes and suffixes), etymology (the origins of words and how this affects spelling) and other orthographic concepts (knowledge of the patterns in how English is written down). If your school teaches all of this rigorously and systematically and your student still experiences significant spelling difficulties, speak with your school’s special education advisor about possible learning difficulties and how you can support your student.

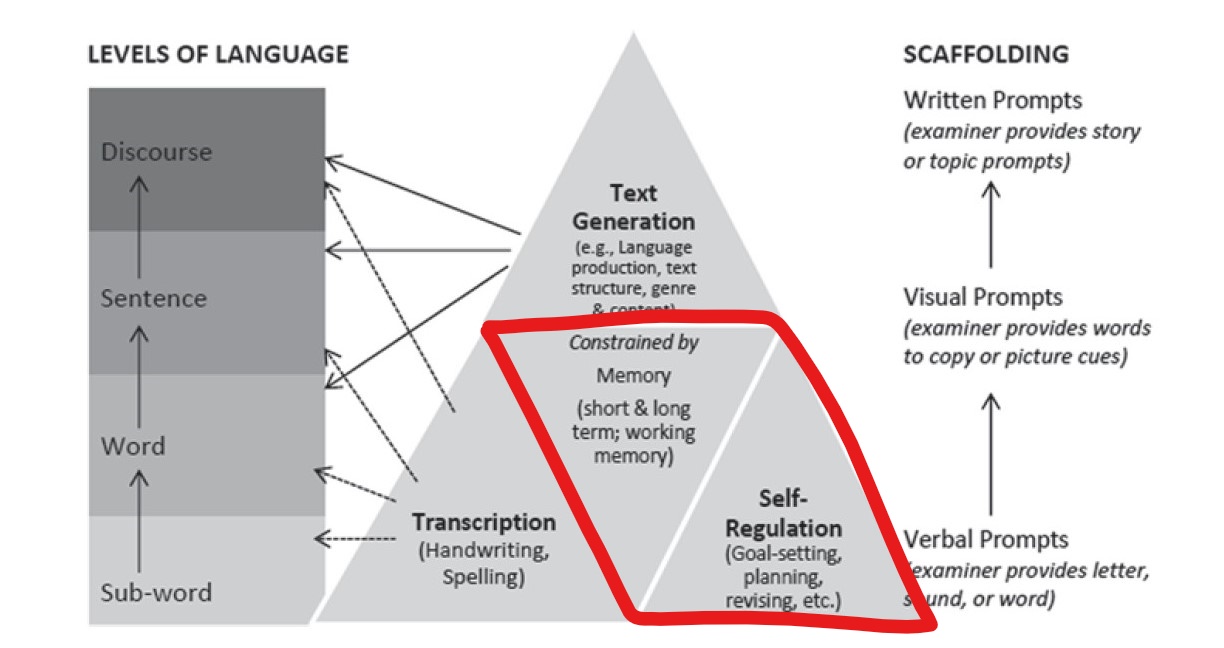

Area of Difficulty 3 - Memory and Regulation

Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (1993). Structural equation modelling of relationships among development skills and writing skills in primary- and intermediate-grade writers.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 478–508.

I have worked with students who could orally share a sentence with me, and then in the 10 seconds, it took them to pick up their pencil and get their book ready, completely forget what they wanted to write. Many children experience working memory difficulty or issues with self-regulation that prevent them from focusing long enough to get ideas down on paper. Depending on the age of the child and the severity of the difficulty, there are several ways to provide support in the classroom.

- Break tasks down into small, manageable chunks

- Use picture prompts that either you provide or the student draws to scaffold ideas. For example, if you want your student to write a narrative, allow them to draw a story map or cartoon and use that to organise thoughts. This means they do not have to hold the entire thing in their head while writing each part.

- Ensure that the student has a firm knowledge of the subject matter before asking them to write.

- Orally practice sentences so that they can have the chance to commit them to memory before writing.

- Use a physical prompt to track the words in a sentence.

- Allow the student to create a voice recording of what they want to write so that they can listen to it as they write. This allows them to skip back and listen as many times as they need to get the words on the page.

- For students with significant difficulties, utilising computer voice-to-text features can be very useful.

- Allow students to type rather than hand write for longer pieces of writing. This removes one of the things that the child will need to think about as they share their ideas.

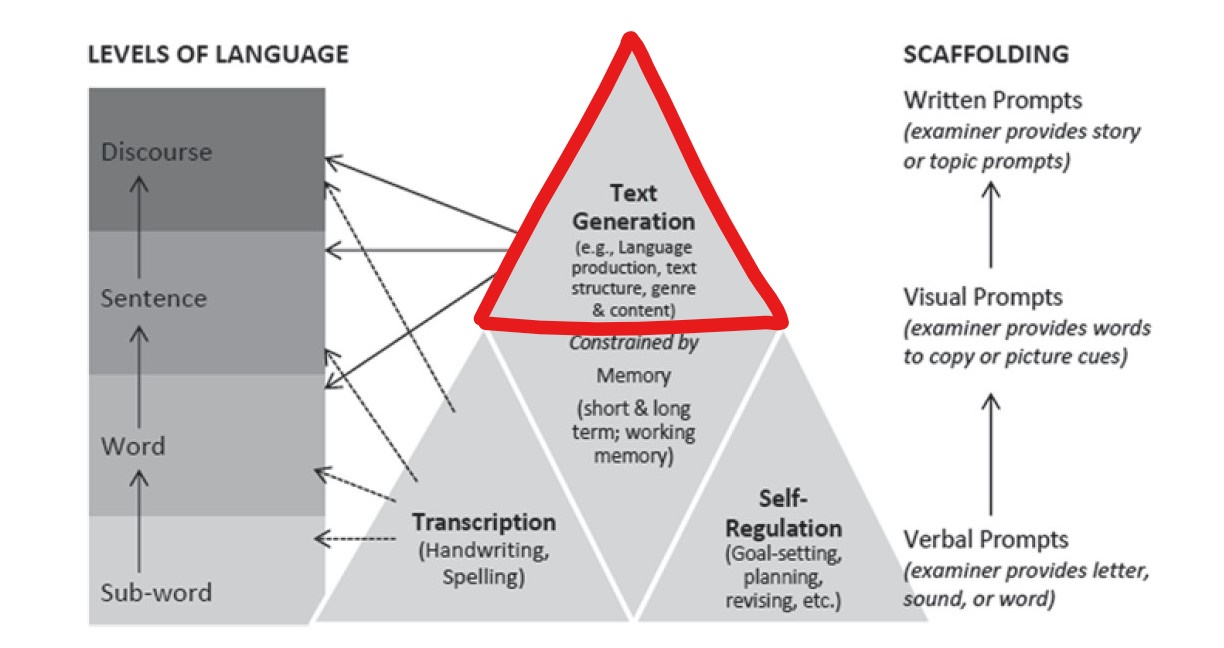

Area of Difficulty 4 - Text Generation

Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (1993). Structural equation modelling of relationships among development skills and writing skills in primary- and intermediate-grade writers.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 478–508.

A typical primary school writing lesson will likely look something like this:

- Teacher presents an example of the text type currently being studied

- Teacher unpacks the text type, pointing out features

- Teacher models writing

- Teacher ‘engages’ the whole class in a joint construction where specific children put up their hands to give ideas that the teacher writes on the board

- Teacher provides a writing template and instructs children to go to their desks and write their own version of what has been created on the board.

- Teacher floats to support less confident children or groups them together to walk them through the process.

For some children, this is sufficient for them to be successful in the lesson. These children are already fairly proficient in writing and are skilled in all of the areas mentioned above, plus they understand how to compose ideas.

However, this process leaves many children feeling helpless, insecure and even angry. Let’s review the steps above in terms of what a reluctant writer might be doing and thinking.

How the reluctant writer thinks

- Teacher presents an example of the text type currently being studied –

“Oh great. I hate writing. I wonder how I can get out of this? Oh look, there’s a piece of paper on the carpet. I could roll it into a ball and throw it at someone. She always makes us do this. I hate it so much. My breathing is a bit fast.” - Teacher unpacks the text type, pointing out features

“Blah, blah, blah. What is she on about? I hate writing.” - Teacher models writing

“Oh good, her back is turned. Hey friend, what are you doing after school this afternoon?” - Teacher ‘engages’ the whole class in a joint construction where specific children put up their hands to give ideas that the teacher writes on the board.

“Please don’t ask me, please don’t ask me. I can’t look stupid if I don’t put my hand up. Ah, my stomach feels tied in knots, and I’m starting to feel upset. Oh good, the smart kids are answering. I hate writing. I’m going to lay down on the mat.” - Teacher provides a writing template and instructs children to go to their desks and write their own version of what has been created on the board. “If I keep laying on the mat, I won’t have to go to my desk. I’ll ask to go to the toilet or get myself kicked out of class.”

- Teacher floats to support less confident children or groups them together to walk them through the process.

“I hate this SOOOO much. I don’t know what she wants me to write. I can’t even do it anyway. I’m so dumb.”

So What’s the Alternative?

Tip 1) Firstly, provide meaningful context for writing. Teaching your students through quality texts (picture books are terrific for all ages) and ensuring that you ‘build the field’ of background knowledge sufficiently before asking children to write anything will ensure greater engagement all round.

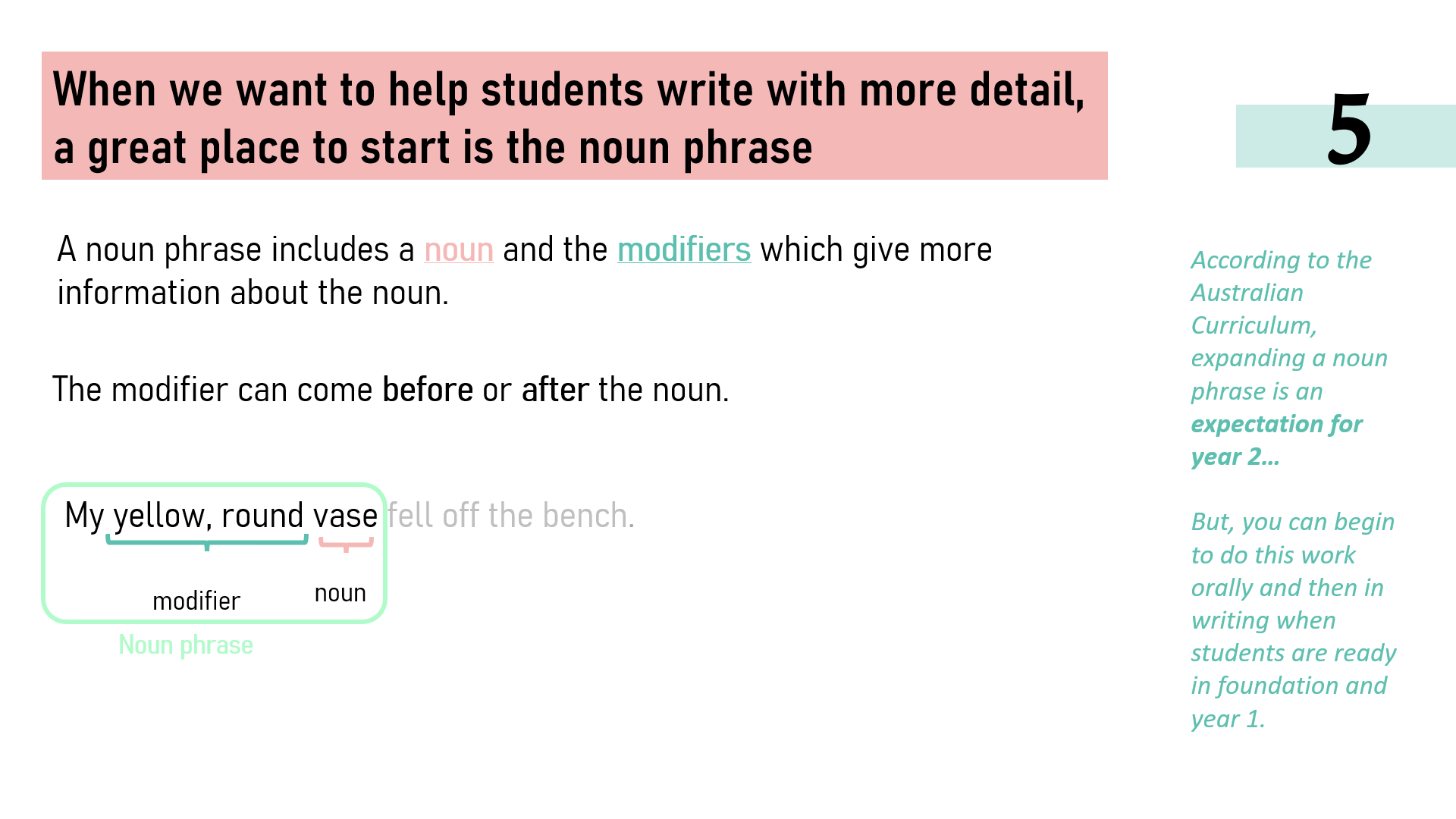

Tip 2) Include lots of sentence level work in your writing program. Sentences are the key to great writing, so supporting students at this level and explicitly teaching sentence structure and sentence writing is a must.

Tip 3) Ensure that every student participates in every part of your lesson in the way that they can. That means that if some of your students can only write single words independently, that’s what they do. If they can only write simple sentences, that’s what they do. If they can write entire paragraphs, that’s what they do. Remember, however, that if your student cannot write on their own, you provide alternative assessments so that you can capture their ideas (such as recording verbal responses on an iPad).

Tip 4) Talk with your reluctant writers before the lesson and make clear what you expect. If you are going to sit with them and support them to get started, tell them. This lets the student/s know that they aren’t going to be on their own and may prevent some of those off-track behaviours.

Tip 5) Break the writing task down into small chunks and group students for the level of support they need.

Tip 6) Provide ample opportunity for students to talk about ideas before asking them to write them down. If you can’t say it, you can’t read it or write it.

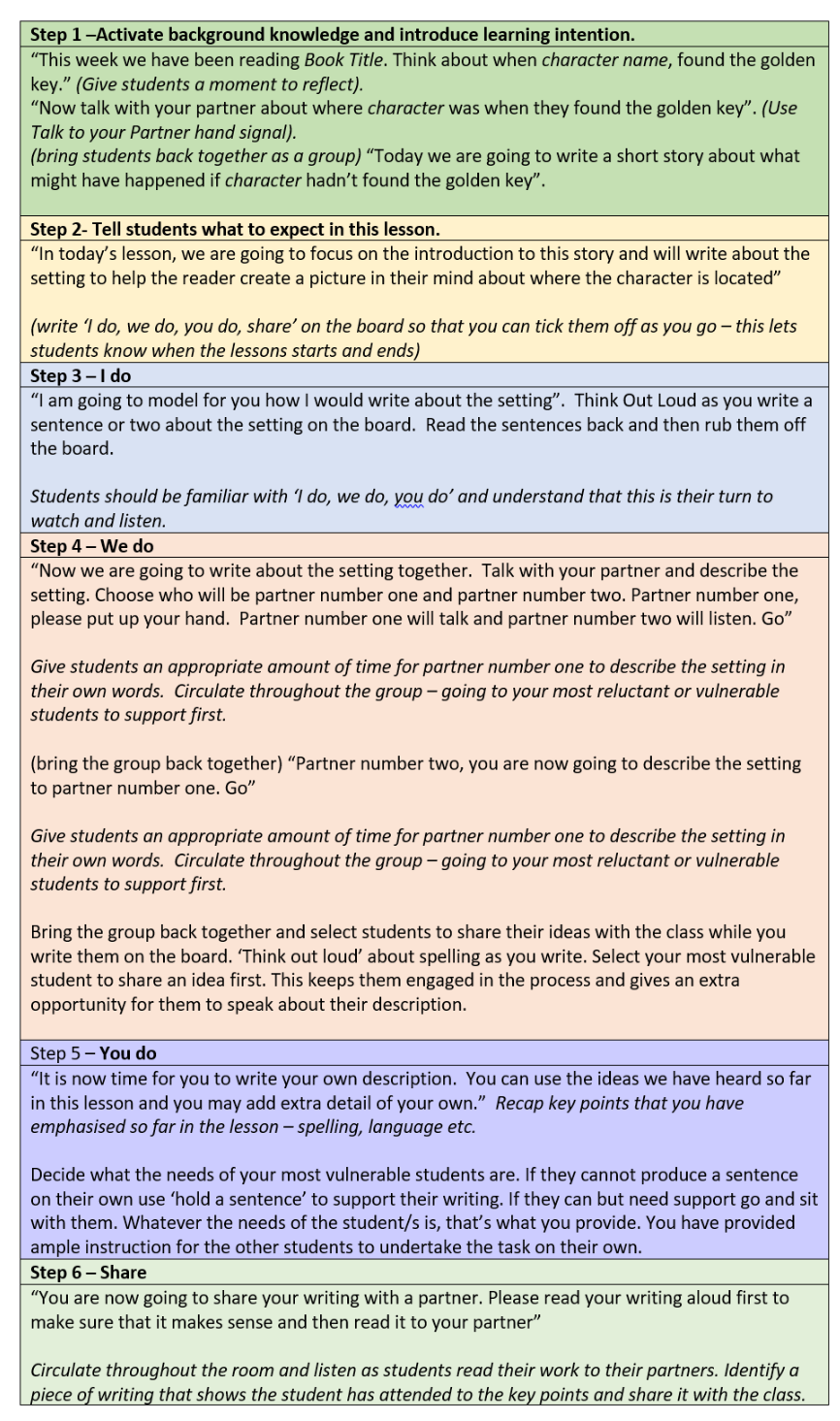

Here is a suggested lesson format for a full-participation writing lesson

Writing is a highly complex task that requires students to perform a range of tasks simultaneously. By identifying the area of difficulty for your students and including instruction to address these difficulties in your teaching program, you will support them in an extremely important way. It is not enough to help them manage without core skills; we need to provide explicit and intentional teaching to enable students to develop these skills and become full participants in literacy at school and in their wider lives. Breaking down writing lessons into manageable chunks and providing strong scaffolding supports all learners, not just those experiencing difficulty. With time, this allows even the most reluctant writer to show what they are capable of.

Looking for ready-made resources to help you implement structured literacy in your classroom? Read more about the Resource Room here.

Jocelyn Seamer Education

Jocelyn Seamer Education

6 comments

This is such a rich, informative and practical post Jocelyn. I love how you present information so clearly and practically (definitely "no-nonsense"!) with deep evidence-based knowledge underlying it. I'm going to share the link with a number of teachers who have been asking about writing. Thank you again for the work you do and your generosity in sharing it.

Thanks, Jocelyn. These blogs are great. I’m currently doing CRT and it’s nice to do some refresher reading. This particular article is pertinent for a recent Year 7 English class of reluctant writers.

Actually verbally modeling the struggle writers encounter in front of the class and personal goal setting are two other major pedagogical factors I would never overlook with a struggling writing.

Thank you for these helpful hints to support teachers with struggling writers.

I often use your material to share with the many teachers I work with. It is easy to understand, informative and most importantly offers great suggestions of 'how' to help children who struggle. It also empowers and upskills the knowledge of our teachers. Thank you so much!!

Leave a comment