8 Ways to Supercharge Your Writing Instruction

Over the past several weeks I have brought you a series of posts about writing instruction. This area of our teaching is one that can leave, even the most confident teacher, feeling adrift. There is so much research and solid information about reading instruction and yet when it comes to writing, there is scant reliable information and guidance out there. In my quest to support you all and your students I spoke with a number of teachers to ask them about their experiences of teaching writing in the first three years of school. Here are the things they said,

“There is way too much emphasis on genre.”

“We are expected to have every child produce a whole piece of text, even when they can’t read all their single sounds yet. It just doesn’t make sense!”

“Our leadership doesn’t really understand where our children are up to and what we need to help them move to the next step.”

“I get much better results when I give children something hands on to do before I ask them to write.”

“Background knowledge is so critical for writing. How can children write about things they know nothing about?”

“There are always students who I just don’t know how to help. I show them over and over what to do, and they still can’t do it. I feel so bad.”

If these statements resonate with you, I hope that it gives you some comfort that you are aren’t alone in your struggles to teach reading. In fact, I remember a time when I felt the exact same way!

To help ease the overwhelm, here are my top 8 suggestions for how to supercharge your writing instruction and move away from feeling confused and frustrated to having a little more certainty in your preparations for term 3.

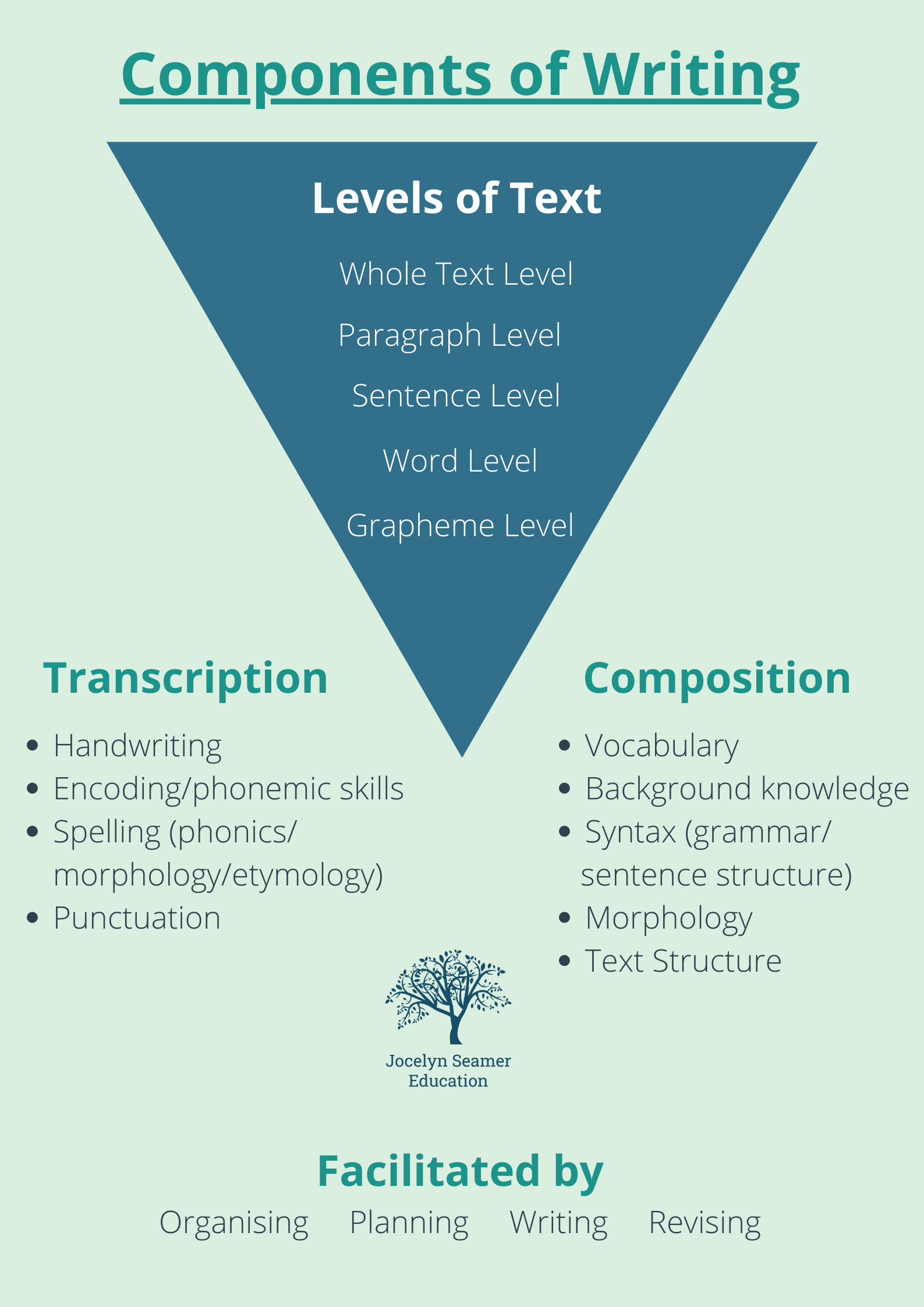

- Get Clear About the Components of Writing

In reading, we have Scarborough’s Reading Rope, but in writing it can be hard to really pin down what we need to include. To help with this, I created a Free Teaching Guide – How to Teach Writing in the Early Primary Grades. You can download a copy of this here.

- Recognise that what we have been taught about what motivates students to write isn’t quite right.

The idea that we increase student motivation to write by making it authentic, fun and engaging is really appealing. After all, we want children’s learning to be something that is done with them, not to them, don’t we? However the suggestion that these factors alone are the key to getting children writing leaves a great number of students out in the cold. In short, children enjoy writing when they can do it. Automatic transcription skills, taught explicitly in teacher lead lessons are critical to helping all students develop the baseline level required for children to put pen to paper and produce something meaningful. You can read more about this in my post ‘The Key to Increasing Student Motivation to Write’.

- Familiarise yourself with what the curriculum is asking of you and deciding how skills and knowledge are best taught. As much as it may make your eyes roll back in your head, examining the curriculum documents to find out exactly what children are expected to do b the end of the school year will give you the knowledge you need to avoid teaching unnecessary content or getting off track. There is so little time in our school days that we really don’t have time to waste in group rotation activities we bought on an online store or downloaded from our favourite teaching subscription website. We need bang for the buck from every instructional moment. For more information about how to teach what, you can read more in my post ‘Creating Order from a Crowded Curriculum’.

- Meet students where they are up to

Regardless of what the curriculum says, if a student can only write CVCs in year 2, we need to meet that students precisely where they are up (which in terms of transcription would be to use those CVCs to write a simple sentence and learn the extended alphabetic code). However, just a because a student doesn’t have the pencil to paper skills yet, it doesn’t mean you can’t (and shouldn’t) include them in all of your grade appropriate writing lessons. What it does mean, is that the student participates orally, is supported with appropriate adjustments, to participate in writing and is only expected to produce writing on their own that matches their level of transcription. I covered some differentiation expectations in my post ‘But he just can’t write a sentence’.

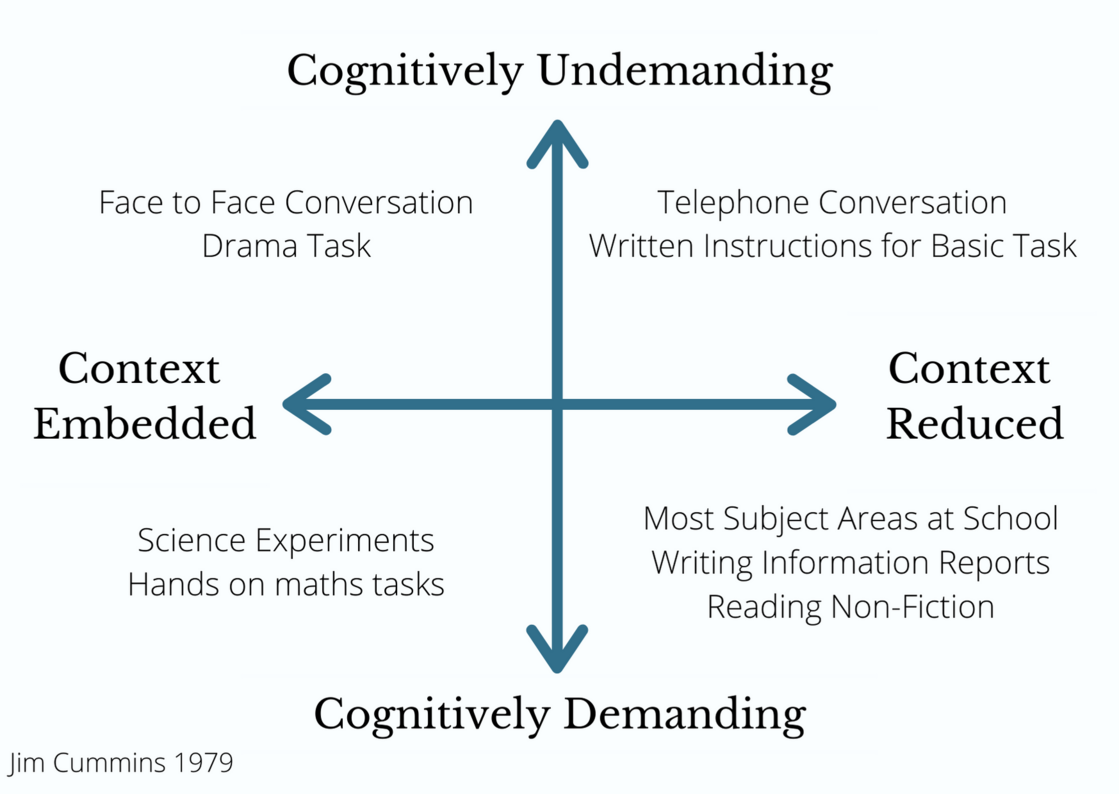

- Focus on creating an environment rich in academic language.

A focus on increasing student talk is wonderful and should include a plan for moving students from basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) to Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP). This idea from Jim Cummins has been around in EAL/D pedagogy for long time, but it has significant implications for the general primary classroom teacher as well. You can read more about it here in my post ‘Sometimes Conversation Just Isn’t Enough’.

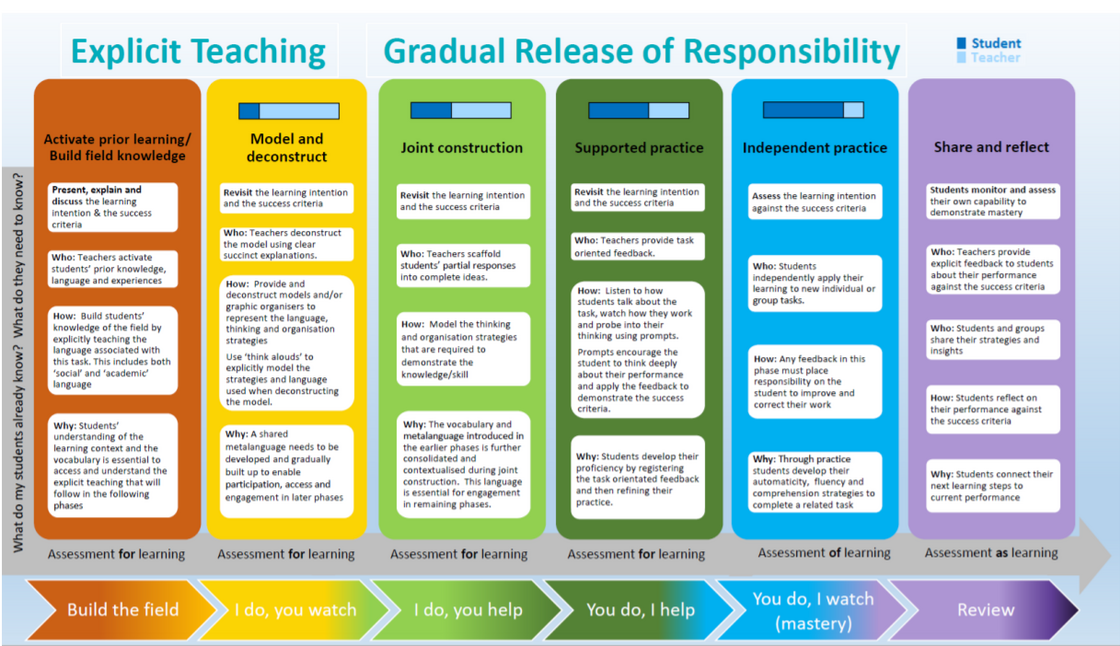

- Make the explicit teaching model your friend.

A strong focus on Explicit Teaching is not just about a surface level of ‘I do’, ‘We do’, ‘You do’. It’s about engaging and including children at every point of the learning process. The aim here is FULL ENGAGEMENT. In the post ‘A Writing Lesson to Engage Every Child’ I outline what it might look to conduct a full engagement lesson in your classroom and provide a lesson structure for you to follow. You can access it here.

- Use high quality literature to model language and text structure for students.

Great picture books provide the jumping off points for teaching grammar, vocabulary and sentence structure. Read more about how to do that here.

- Create a system for teaching

Trying to reinvent the wheel every time you want to teach writing is crackers. It leaves both you and your students lost and uncertain as you work to help them master this highly complex skill. Having a system in place with clear steps and progressions means that you can cut down your planning time, collaborate with colleagues to share inspiration and the prep and support students with familiar, predictable routines. When you teach with predictable, repeatable routines, children can focus on learning because they don’t spend their time thinking, “I wonder what I have to do here”. They know what is coming and can trust that they are going to be successful.

Jocelyn Seamer Education

Jocelyn Seamer Education

0 comments

Leave a comment